Federal Focus- The Burden on Child Welfare’s Data Backbone

Why Federal Stewardship Matters More Than Ever

By Kurt Heisler, PhD

Data systems quietly hold up the daily work of child welfare. The federal infrastructure behind those systems now faces an uncertain future.

The White House’s recent child welfare Executive Order Fostering the Future for American Children and Families calls on states to modernize their state child welfare information systems by improving data collection and integration, strengthening outcome-tracking platforms, and expanding the use of AI and predictive analytics.

At the center of all of it is the Comprehensive Child Welfare Information System (CCWIS) — the federally financed digital backbone that supports child welfare case management, data sharing, and federal reporting.

CCWIS is financed through Title IV-E at a 50 percent federal match — essentially cutting the cost of system development and operations in half for states.

But even as the federal government calls for stronger, more modern systems, the future of federal stewardship for CCWIS is in flux.

Reorganizations and reductions in staffing are creating pressures on the federal capacity to support states in this work, right as the federal expectations bar is rising.

Understanding why CCWIS oversight matters — and what’s at stake without it — is now essential.

What CCWIS Makes Possible, From the Frontlines to Policy Decisions

To understand why CCWIS stewardship is so critical, let’s start with what effective CCWIS support and implementation can make possible.

More informed individual casework decisions. Real-time access to complete family histories, caregiver risk factors, and current case status enables better, faster decisions.

CCWIS data sharing means a worker can see what led to the child entering foster care, services previously recommended and delivered, if the child is struggling in school, and what community supports exist.

More effective family finding. Modern systems map extended family networks, flag kinship caregivers, and track sibling connections — the difference between keeping families connected and separating them.

Tracking outcomes that matter across a jurisdiction. CCWIS requirements push beyond casework compliance and allow agency leadership to track jurisdiction and state-level outcomes like maltreatment recurrence, educational stability, mental health, placement changes, and time to permanency.

This lets agencies monitor how children are faring and know where and when reforms are needed.

National data to shape public policy. National data from AFCARS, NCANDS, and other systems depend on state CCWIS implementations.

Better state systems generate better national data, shaping federal policy and providing evidence for policy and practice improvements.

The Long Road of Implementation

CCWIS became the federal IT model in 2016. Although participation is technically optional, states that adopt CCWIS receive enhanced federal funding — prompting many to opt in.

At the same time, CCWIS carries additional requirements, which has led others to decide against it.

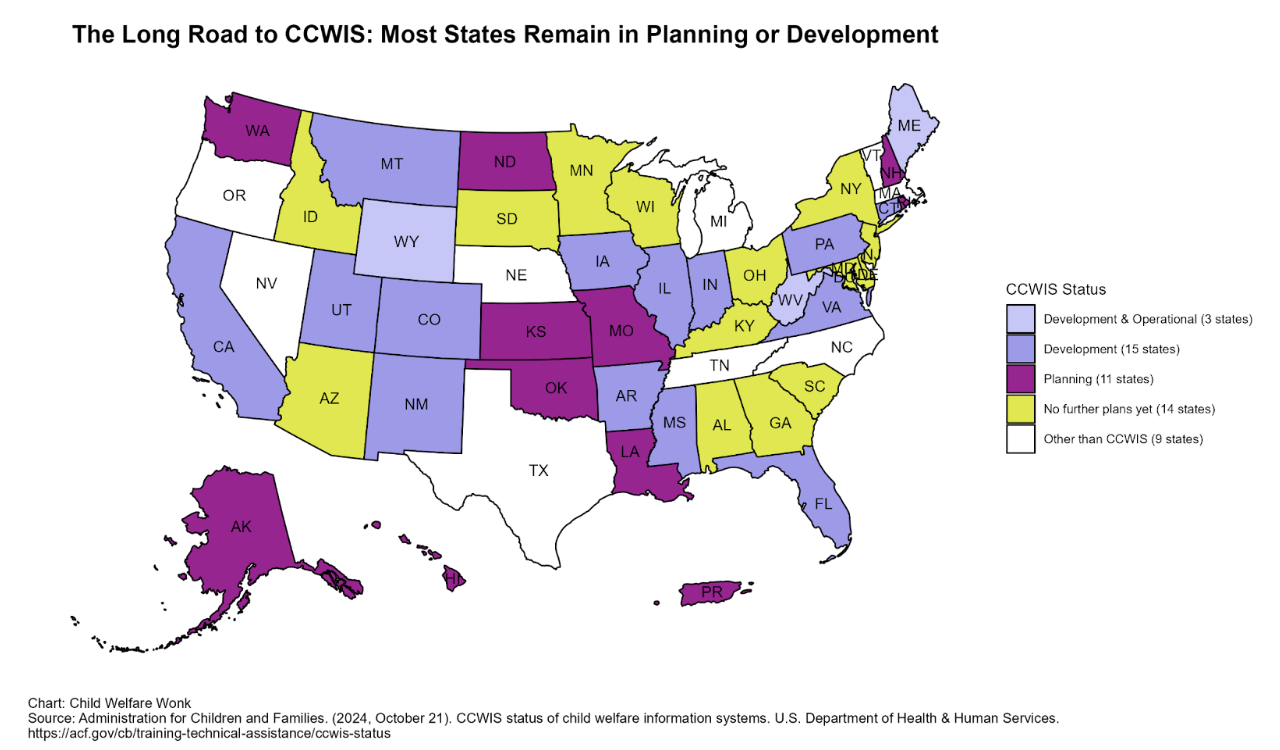

Nearly a decade later, 43 states (including DC and Puerto Rico) have “declared” a CCWIS, but progress varies widely:

Only three states are close to full operation, with most major functions already implemented (Children’s Bureau calls this, “Development and Operational” or “DEV+OP”)

15 states are actively building their systems. They have federal approval to begin development and are working with vendors and internal teams to bring the new system online (“Development”)

11 states are still in the early planning phase and have received federal approval to map out their system design, timeline, and budget (“Planning”)

14 states have no further development plans at this time

None of the 43 CCWIS states is considered fully Operational.

Why Implementation Takes So Long

Building CCWIS has consistently been harder than anticipated. Common issues include:

Cost overages. Projects routinely exceed initial budget projections, sometimes by tens of millions of dollars.

Building a CCWIS requires stitching together decades-old legacy data, modernizing infrastructure, redesigning business processes, and meeting a long list of federal requirements — all while keeping the existing system running.

As new needs emerge, requirements are clarified, or technical issues surface, states often have to expand scope, extend contracts, and add functionality they hadn’t fully anticipated in the original budget.

Delays. Timelines that were planned for 3 to 4 years stretch to 5, 6 or longer.

For example, North Carolina’s system has faced almost a decade of delays and false starts, hitting technical challenges and user frustrations that required fundamental redesigns mid-stream.

Many states have faced staffing turnover and budget shortfalls that disrupted projects just as critical decisions needed to be made.

Maintaining CCWIS designation. A few states, like California, have lost CCWIS designation, meaning their federal reimbursement rate drops from 50 percent to 26.5 percent.

This can happen if the state fails to make progress in line with the schedule and plans approved by ACF. This forces difficult budget conversations about whether and how to continue.

The problems above aren’t easily classified as state or vendor failures: they’re the reality of complex IT modernization in a field where practice and requirements vary significantly across jurisdictions and programs.

Designing a single statewide system that fits dozens of workflows and integrates data from courts, schools, and health systems adds layers of complexity.

And because implementation takes time, policy priorities, resources, and federal requirements can shift mid-way, requiring major adjustments.

Federal Stewardship in Flux

Federal stewardship has always been central to CCWIS implementation and progress. States rely on federal partners not only for enhanced financial support but also for the technical expertise, clear guidance, and consistent oversight needed to modernize decades-old systems.

Historically, the Division of State Systems within the Children’s Bureau provided this support. They review implementation plans, interpret standards, troubleshoot technical issues, and approve enhanced federal funding.

This structure created consistency: predictable reviews, clear expectations, and a stable point of contact for states making long-term, high-stakes investments.

What’s Changing — and Why It Matters

That structure is now in flux. The Division of State Systems has been eliminated under a broader HHS reorganization, and five regional offices have been closed.

For now, the work is being absorbed elsewhere in ACF, but the long-term home and capacity for CCWIS oversight remain unclear.

ACF may reassign responsibilities within HHS, expand contractor-based support, or narrow the scope of assistance available to states. Until then, states face uncertainty about where guidance will come from, how consistent it will be, and how it will affect their timelines and budgets.

This uncertainty has material consequences. CCWIS projects hinge on the enhanced 50 percent federal cost share; without clear guidance and a predictable review process, states face a higher risk of losing their CCWIS designation — and with it — the enhanced reimbursement rate.

Few states can absorb the cost of a $100+ million system at the non-CCWIS rate of 26.5 percent.

There’s also a national data implication. Federal datasets like AFCARS and NCANDS — to name a few — rely on CCWIS.

Fragmented oversight can lead to uneven data standards and weaker national data, limiting policymakers’ ability to understand trends or assess reforms.

Sustained federal stewardship is the foundation that keeps CCWIS modernization financially feasible, technically sound, and aligned with national priorities about child and family well-being.

What To Watch, and Why

For new ACF leadership: States need clarity on who holds CCWIS stewardship responsibilities, how approvals work, and what timelines to expect. Without this, even well-planned projects face avoidable delays and budget risk.

For states: Uncertainty around federal support complicates planning. Agencies should explicitly confirm new points of contact, review updated processes, and avoid assuming continuity with prior procedures, especially when seeking guidance or reassessment.

For advocates: Many high-priority reforms require data infrastructure that doesn't exist yet. Tracking disparities, monitoring emerging needs, evaluating prevention services, and using AI and new tech to support casework all depend on functional CCWIS. Supporting state implementations can advance policy without new legislation.

For researchers: National data quality depends on state CCWIS progress and consistency. Fragmented federal oversight could introduce variation in data quality, gaps in required reporting, and less reliable national trends.

A moment for federal recalibration. Even with years of federal support and a 50 percent IV-E match, CCWIS implementation remains uneven and slow across the country.

This suggests that the traditional TA and oversight model was not meeting the needs of today’s systems, even before any changes to federal staffing and contracting.

New ACF leadership, states, advocates, and researchers all have a stake in a clearer, more modernized federal framework — one that provides consistent guidance, strengthens technical capacity, and supports states through complex, multi-year modernization.

Data Infrastructure Compounds

Data systems compound over time. Strong systems get better as staff test them and give feedback, integrations deepen, and accumulated data enables richer analysis.

Systems left half-built degrade through technical debt and workarounds that make them harder to use and harder to trust.

CCWIS represents substantial federal investment: billions in enhanced funding and years of institutional expertise in guidance and oversight.

Whether the knowledge once held by the Division of State Systems was successfully transferred, reorganized into capable hands, or lost will shape what states can accomplish next, and what the next generation of child welfare IT will look like.

Operational details will become clearer over time.

But uncertainty has its own costs: projects slow, questions linger, budget planning becomes harder.

For a field that depends on reliable data to make decisions about children and families, clarity about infrastructure supporting that data is not optional — it is essential.

Kurt Heisler is a nationally recognized expert in child welfare data, policy, and practice with over 25 years of experience helping agencies improve outcomes for children and families. He is the Founder and President of ChildMetrix.