Financial Support for Kinship Care: Where Resources and Rhetoric Diverge

Financial Support for Kinship Care: Where Resources and Rhetoric Diverge

By Susan Smith

Kinship care has always been the quiet backbone of America’s child welfare system.

Long before “foster care” was a system, relatives stepped in to care for children during family crises.

Today, they continue to do so– often without the legal recognition, financial assistance, or supportive services afforded to licensed foster parents.

In 2024, relatives comprised 39 percent of foster care placements and 27 percent of exits from care.

Even more children live with relatives informally, outside the systems count.

The rise of formal foster care following enactment of the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act (CAPTA; P.L. 93-247) brought child welfare into federal focus, prompting an influx of children into state custody. (For more on CAPTA, see the Wonk’s overview here).

This led federal and state policymakers to embrace kinship care, which was preferred by families, supported by advocates, more feasible for caseworkers, and more cost-effective for legislators.

But while practice moved kin to the front of the line, money has lagged behind.

Kin First, Paid Last

As foster care use expanded, the Supreme Court’s 1979 Miller v. Youacum decision opened the door for states to designate relatives as foster parents. The result: a surge in kin placements.

But many relatives were never licensed.

In 2024, 22 percent of foster care placements were with licensed kin, while 17 percent were with unlicensed kin (Table 1).

Put differently, just over half of children placed with relatives had caregivers who were licensed.

Why? Licensing takes time, training, resources, and political will.

For states, licensing kin often means paying relatives foster care subsidies at the same rate as non-relative foster parents and may require relaxing safety standards.

And well-intended licensing standards can become a barrier when the only thing preventing grandma from stepping in is the number of bedrooms in her house.

The structural tension is clear: kin are often the preferred placement, but they are still the last to get paid.

Hiding in Plain Sight

Child welfare quickly embraced kin as resources for placement and permanency, but providing financial support for kinship caregivers was slow to follow.

In practice, many agencies steer relatives toward voluntary or unlicensed care, celebrated as kin-first engagement even when it means bypassing payment and services.

This so-called “hidden foster care” refers to relative placements that occur after a maltreatment allegation but without opening a dependency case and going to court.

While you will often hear stakeholders discourage the practice, practically there is seldom differentiation between licensed and unlicensed kinship care.

The issue is not simple to resolve; more regulation of kinship can increase court involvement and mandate caregiver licensing, things that may disincentivize relatives to provide care.

Yet being subsidized for the costs of providing care is also a strong incentive for licensure.

How Many Kids are Impacted?

The scale is not small.

Although children in hidden foster care are not included in federal data around placements, researchers estimate that between 100,000–300,000 children are placed annually in hidden foster care or diversion.

That’s comparable in scale to the official foster care system.

Meanwhile, federal data show how many children in care are placed with relatives — and how many of those relatives remain outside the licensed system.

According to new 2024 AFCARS data—the second year to distinguish kin licensing status—about 127,000 children were placed with relatives, comprising 39 percent of foster care placements.

One in five (22 percent) foster care placements are with licensed kin caregivers.

Just over half of formal kin caregivers nationwide were licensed in 2024.

The Geography of Kinship Care

States decide whether and how to license and pay their kinship caregivers, resulting in large differences across states.

Despite federal incentives to increase licensing, some states have been slow to license kin, likely due to the added cost to pay caregivers and the effort and political will involved in changing statute to amend licensure standards.

In most cases, licensed caregivers receive some financial assistance and supportive services.

Some states require kin to complete standard foster care training to be licensed, and they are treated like any other foster parent.

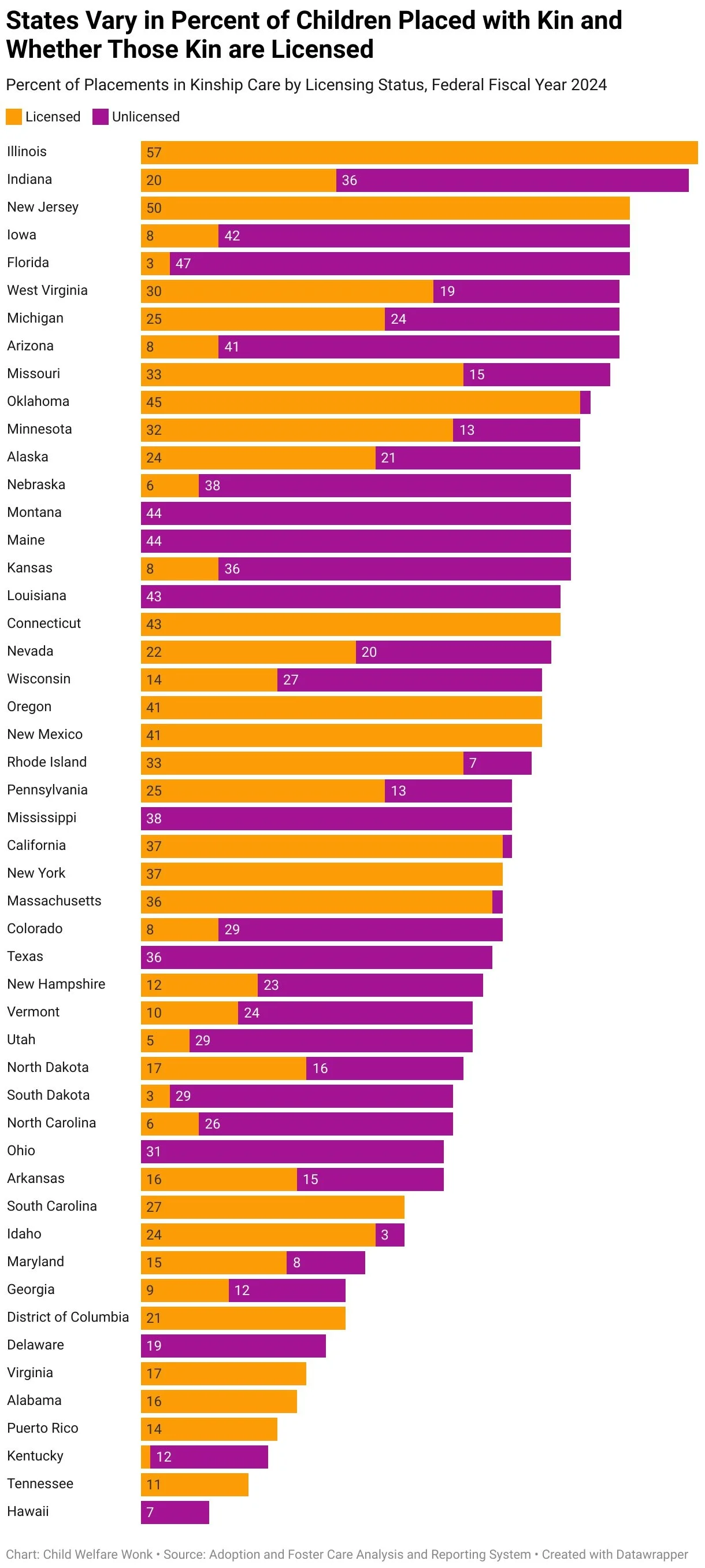

Some of this variation is depicted in Figure 1 (see an interactive version here).

The contrast is stark.

Illinois (57%) and Indiana (56%), are the states most reliant on kinship care for placements, whereas Hawaii (7%), Tennessee (11%), Kentucky (13%), and Puerto Rico (14%) are the states least reliant.

Illinois (57%), New Jersey (50%), and Oklahoma (45%) stand out for having the highest shares of kin placements that are licensed.

Florida (47%), Louisiana (43%), Maine (44%) and Montana (44%) rely heavily on unlicensed kinship care

What Decision Makers Need to Know

Inclusion of data on licensing in AFCARS presents opportunities to better understand differences across placement settings.

From these data in prior years, we know that children in kinship care go home more quickly and move less often.

It should be possible to answer the critical policy question of whether licensing matters for those outcomes.

State leaders face a structural bind: licensing kin unlocks federal funds but commits state dollars, while keeping kin unlicensed saves money up front but shifts costs to families.

Funders should see that unlicensed kinship care isn’t a cost-free solution; it masks unmet needs and creates hidden liabilities that may surface in instability or later system involvement.

Advocates and practitioners need to understand the geography of inequity: two children in identical circumstances may receive vastly different support depending on state policy choices.

Hill staff and federal policymakers should recognize that national averages obscure wide state variation.

The federal role is limited to incentives, but those incentives land unevenly, with real consequences for who gets counted, supported, and seen.

Susan Smith is the Founder of Data Advocates, LLC. Before her consulting work, she spent 16 years at Casey Family Programs, serving as Senior Director of Data Advocacy.