Decoded: So Many Investigations, So Little Service Delivery

So Many Investigations, So Little Service Delivery

By Laura Radel, Senior Contributor

Every year, millions of Americans call Child Protective Services (CPS) hoping a family will get help.

Researchers have estimated that 37 percent of all US children — and 53 percent of Black children — experience a CPS investigation during their childhoods.

Yet despite how pervasive CPS investigations have become, they rarely result in services to families.

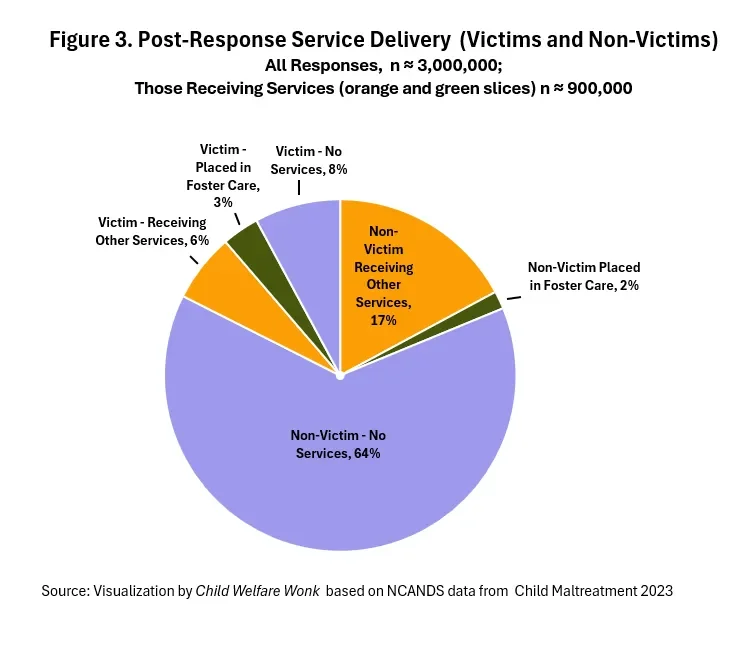

Of children referred to CPS, just 11 percent received any services in 2023.

Even among children confirmed to be victims of maltreatment, nearly half receive no services beyond the investigation itself.

The result: a system that investigates at industrial scale, but delivers support sparingly.

The Scale

Every state requires certain professionals — typically teachers, clinicians, child-care workers, social workers, and law enforcement — to report suspected abuse or neglect of children to a hotline.

The threshold to report is usually reasonable suspicion of abuse or neglect, not proof.

Some states extend reporting requirements to all adults. Training and penalties push reporters to err on the side of calling. The front door to CPS is built for volume.

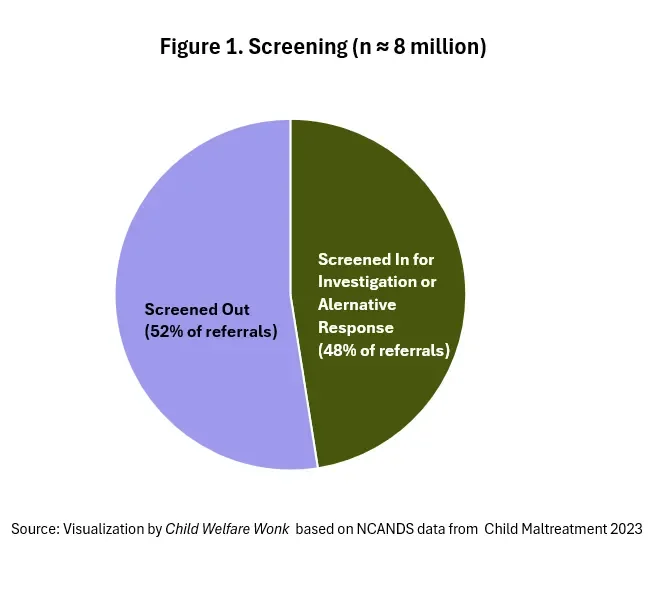

In 2023, almost 8 million children were referred to CPS.

Of these, about 3 million (48 percent) were “screened in,” which means they received either an investigation or an alternative response. The rest were screened out.

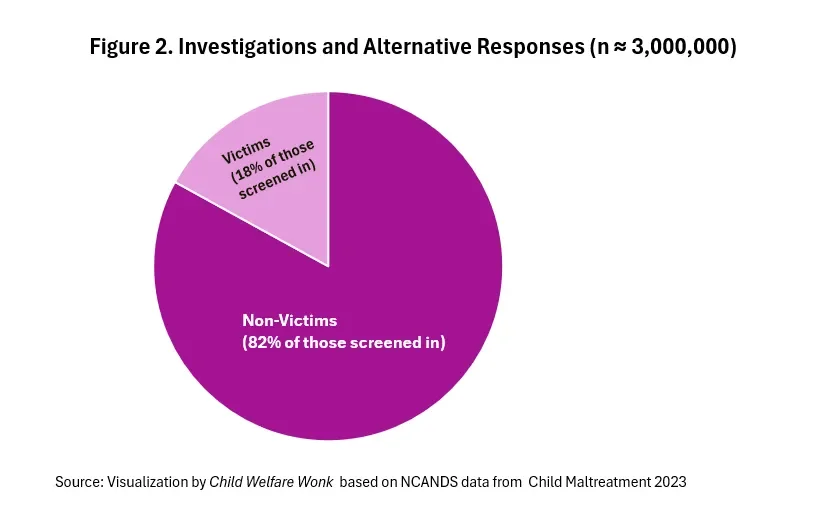

Of those 3 million children that were screened in, about half a million were determined to have been victims of maltreatment– which amounts to 7 percent of initial referrals and 18 percent of those screened in.

Of the roughly 540,000 children determined to be victims, almost 20 percent (105,000) were placed in foster care.

An additional 35 percent receive services other than foster care (about 200,000 children).

And for the remaining 44 percent of children — nearly 250,000 — determined to have been victims of maltreatment?

Their cases were closed without any service being delivered beyond the investigation itself.

Some non-victims also receive services. About 2 percent of non-victims are placed in foster care (about 40,000 children) and about 21 percent (547,000 children) receive other services.

Nearly 80 percent of children determined to be non-victims receive no services (nearly 2 million children).

That imbalance isn’t confined to confirmed cases. It defines the entire system: of all children initially referred to CPS, just 11 percent received some service.

Agencies are doing a lot of screening and investigation and providing relatively little service to help children and their families.

It’s important to stress that not every child who has experienced maltreatment needs further services from the child welfare system.

For instance, in some cases, by the time an investigation concludes, the perpetrator has either left the household or was never a part of the household in the first place, and the situation has been addressed by the family or law enforcement.

But most perpetrators are parents and it’s hard to imagine that in most cases investigations alone address the potential for future harm.

In many instances a child will receive several referrals and investigations before CPS intervenes.

In 2023, about 13 percent of child maltreatment victims had in the past 5 years received family preservation services and 4.5 percent had been previously reunified from foster care.

In addition, roughly 10 to 12 percent of children who died from maltreatment had received family preservation services in the past five years and approximately 3 percent had been reunified from foster care.

The annual Child Maltreatment report does not indicate how many children who were fatally maltreated had a prior report or investigation without having received services.

Is This the System We Want?

Mandatory reporters have been trained to make referrals any time they’re concerned about a family, and many say they report in the hope that a family will receive supportive services.

But the data makes clear that that’s not what happens. The system they reach is designed to respond, not to resource.

This is not a new revelation. But solutions have been hard to materialize, and each comes with tradeoffs policymakers have been unwilling, or unable, to resolve.

Options include:

Narrow the front door

What it looks like

Tightening criteria for reports and investigations, or changing who reports and why.

Rationale proponents raise

CPS is currently screening and investigating too many families, particularly those at low risk.

Tradeoffs

Narrowing intake is a low-cost option, but risks missing children in need of protection.

And reporters often argue they want a support system that is equally responsive as a hotline, to ensure connection to services.

While maltreatment related fatalities remain rare events, they have risen somewhat in recent years as the foster care population dramatically declined.

Since the most recent foster care peak in 2018, the number of children in foster care has declined by about 20 percent (down nearly 100,000 children from 2018 to 2023, though two states did not report AFCARS data for 2023 so a complete total is not known).

In that time the annual number of child fatalities increased by about 230 children, or 13 percent.

Build prevention outside of CPS.

What it looks like

Invest in primary prevention — home visiting, mental health, early care, family stabilization — before families ever reach CPS.

Rationale proponents raise

Expanding services here would make families more likely to use services, and could get better outcomes at lower cost.

Tradeoffs

Families benefit, but services are expensive and may not address more severe forms of maltreatment or provide sufficient ongoing services to address chronic or recurring problems.

In addition, the service delivery infrastructure for preventive services may not exist in many communities.

Redesign response inside CPS.

What it looks like

This includes Alternative Response programs, which add one or more non-investigative tracks for low or moderate risk families.

Rationale proponents raise

They aim to de-escalate contact and connect families to voluntary services, reducing maltreatment and improving outcomes.

Tradeoffs

But, these efforts have shown mixed results, at least in part because the service menu behind them is often thin.

Strengthen treatment for higher risk families.

What it looks like: Offering dedicated services to reduce risk when foster care is likely or imminent, a la Family First.

Rationale proponents raise: After maltreatment is found, services for parental substance use, mental illness, and domestic violence, can stabilize many families.

Tradeoffs: However, quality services intensive enough to meet families’ needs are in short supply in many communities.

In addition, services following a finding of maltreatment are inherently coercive and prioritizing families referred by CPS could displace other high-need groups, such as homeless individuals and those referred through the criminal justice system.

So, What Now?

The data tell us that we are asking the CPS system to do contradictory things.

The question is whether, by investigating so often and providing services so infrequently, we are getting the outcomes we seek?

The choice is not between reforming CPS or abandoning it.

Those simple platitudes abdicate the harder challenge and responsibility of determining what we — as a field, in our states and communities, and as a nation — want the system to achieve.

Why and how do we want to achieve those outcomes, and with what non-negotiable elements?

Only when we determine those things can we better align the system to achieve a set of outcomes we seek through policy and financing.